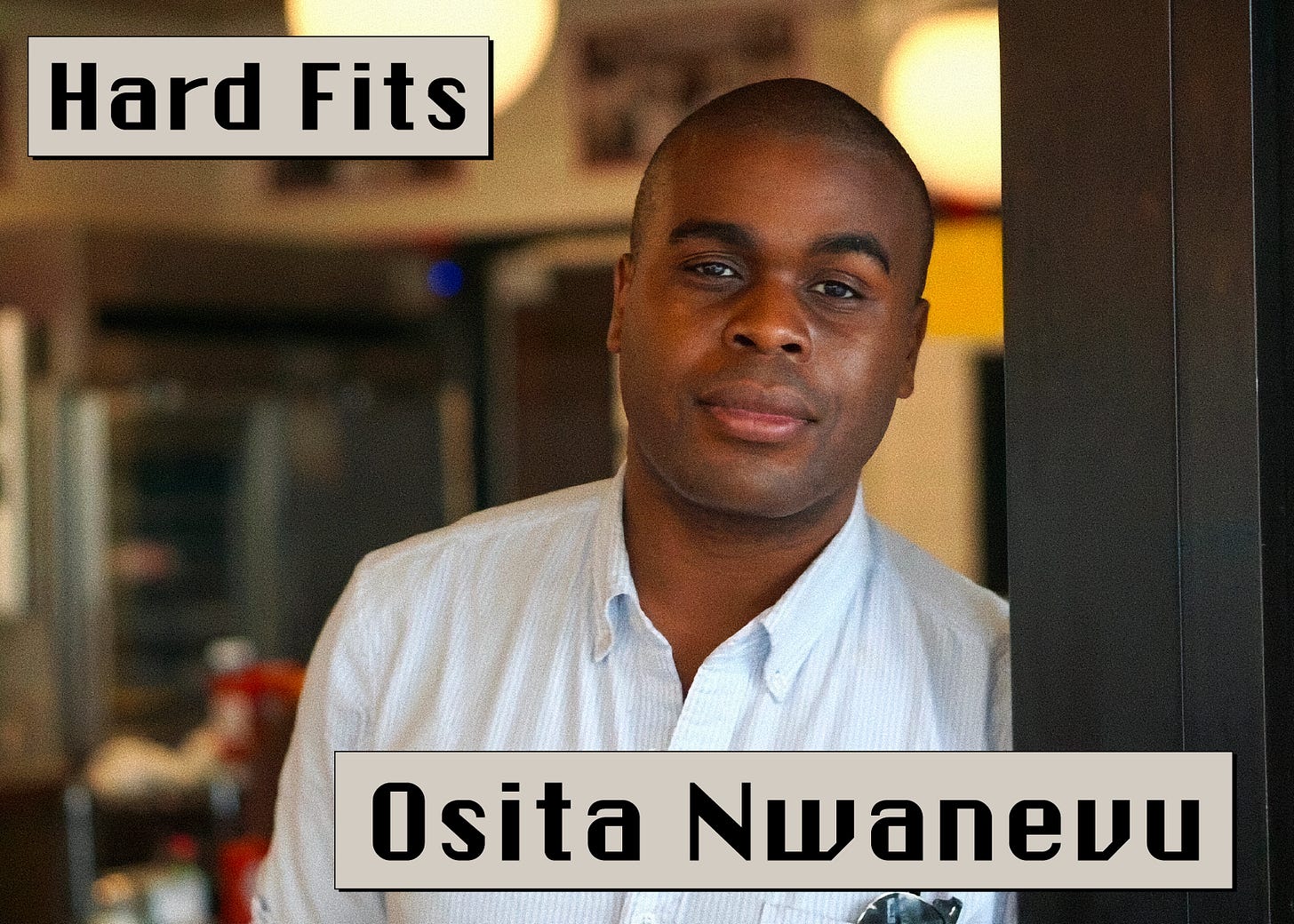

Hard Fits: Osita Nwanevu — Part 1

The political savvy of Zohran Mamdani’s style, the phoniness of John Fetterman, and the flattery of being mistaken for a Republican

Welcome back to Hard Fits, an interview series about menswear and the men who wear it. Today’s subject: author and journalist Osita Nwanevu.

I’ve been a longtime admirer of Osita’s work in outlets like The New Republic and The Guardian, where he writes about politics and current events from a left perspective. The clarity of his prose and his thought process is striking, particularly in this era of slop and obfuscation. His new book, “The Right of The People,” is an excellent (and exceedingly readable) primer on the antidemocratic history of these United States, as well as the mechanisms by which we might bring about a brighter, more democratic future.

Fortunately for me, Osita is also interested in style—both his own and that of the American political class. Recently, we connected to review the sartorial state of the union, from Donald Trump’s authentic inauthenticity to Zohran Mamdani’s sack suits to John Fetterman’s wretched basketball shorts. What follows is an edited transcript of the first part of our conversation.

Alright, so I’m hoping to give you an opportunity here for a slightly more lighthearted conversation while making the media rounds. But just to start things off, can you deliver a quick hit thesis summarizing what you’re saying in the book?

So I think the 3 major points I'm trying to make in the book are one, democracy is good, two, America is not a democracy, and three, America should be a democracy. That’s the book in the tightest possible nutshell. It’s an exploration of what democracy means through an analysis of our political and economic institutions, and you hopefully come away with a sense that democracy is a project that is ongoing.

“Democracy is good”—that’s a fascinating concept.

It’s a contestable claim nowadays.

Well it’s a fantastic book. In the intro, you write, “democracy has become a specious and suspicious platitude, equally useful to marketers and would-be dictators—a hollow idea for a hollow, unserious time.” I can’t help but feel that statement applies to the sartorial senses of those in the political class as well.

Well, I think politicians have been dressing badly for a long time, certainly as long as I can remember. I think there used to be an age when people put more effort into their appearance, but I think in the last thirty to forty years—and nobody should quote me on this as a historian—there’s been a move towards looking like the imagined “Everyman” as best you can. You’re registering that you’re not a millionaire, or whatever you really are, by making certain choices about how you dress.

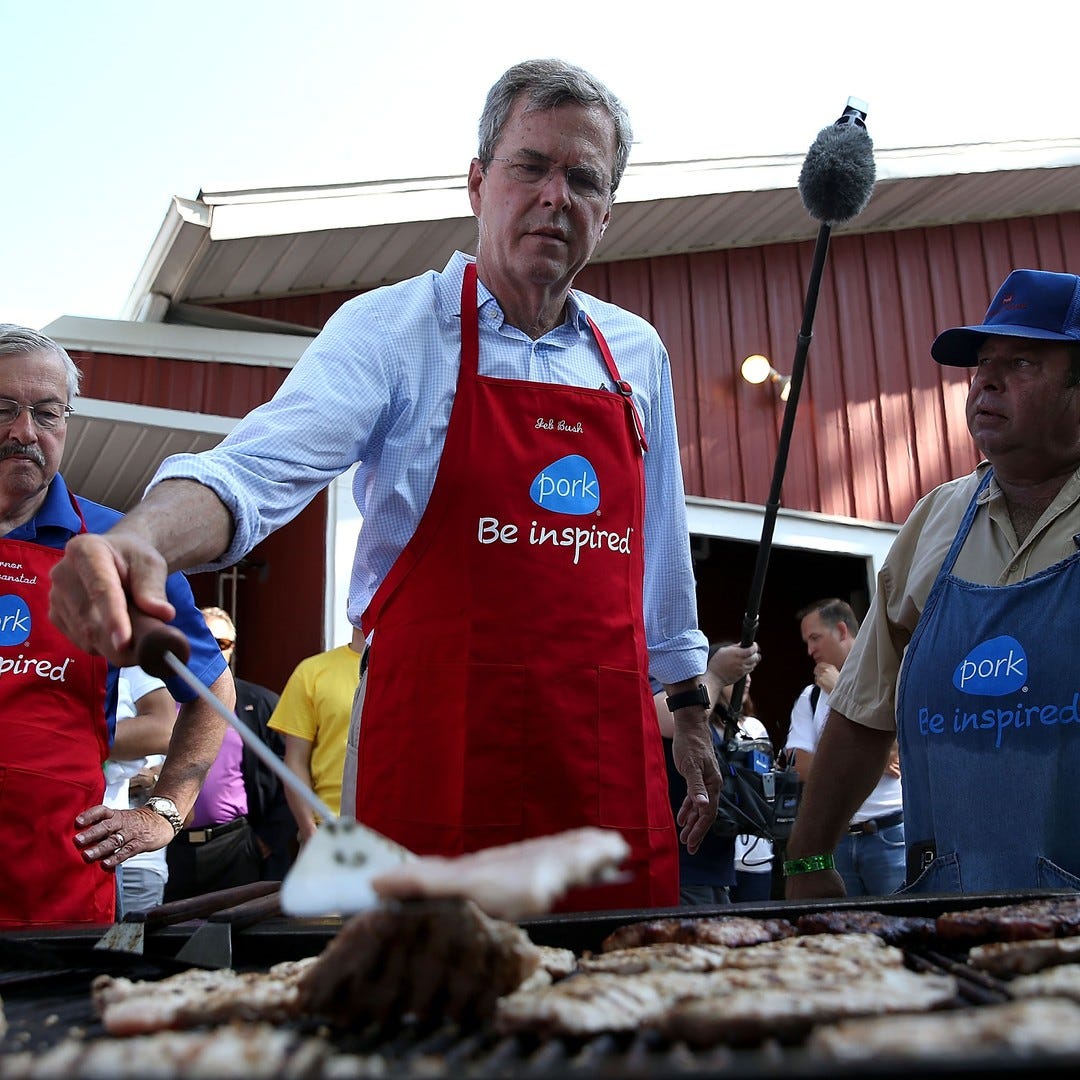

Men will go to the Iowa State Fair, for instance, and not wear a jacket. They’ll have this button down shirt that they’ve rolled up to their sleeves and that fits terribly, and that’s kinda the classic look now. Going back fifty, sixty years, you didn’t really see as much of this. There’s been a real effort to elide and erase the real differences that separate politicians from ordinary folks by making certain sartorial choices.

The other place I think this connects with the book is y’know—the conception of democracy I have here is one that I’m trying to broaden beyond “you should have the right to vote,” which is obviously important. But I try to talk about democracy meaning that we have the agency to shape our lives. That’s why we deserve the right to vote, and that’s also why we deserve rights as workers. It’s a conception of human life where you really take for granted our ability to determine what our values are, what we find interesting and important. We want to express ourselves as true individuals, not just people who are beholden to certain hierarchies based on the context in which we happened to grow up. We can make active choices about what matters.

These are all things that matter when it comes to style. The way that you dress is an expression of who you really are. The world that I imagine is a world where more people—all people, hopefully, not just the rich—can really express themselves and live the lives that they want to and have access to beautiful things.

I’m somebody who’s on the left, and I think that people often have this misconception of the left—that it’s about a kind of dour seriousness, that we’re anti-fun, that we want everybody to eat the same grey gruel at the end of the day, because that will fight inequality. That’s not what it’s about for me. I’d like a world where more people have more access to beautiful things, and I think that’s certainly an element of how I think about style.

On the note of dressing like the “Everyman”: Donald Trump is obviously a very notable exception to this rule. I wonder what your read is on his sense of style, which on one level is very clear and powerful, but which on another level bears almost no resemblance to the types of people that tend to vote for him.

I mean, I think one of the things that was so shocking about his first victory in 2016 is that he broke all the rules you’re supposed to follow. He didn’t do this whole song and dance of, “I’m not gonna wear a tie, I’m not gonna wear a jacket, I’m not gonna go out there in blue jeans.” I can’t even imagine Donald Trump in blue jeans. It’s like a photo of Bigfoot.

But that’s not the image of him that people carry in their minds. Many people who voted for him liked him because there’s this perceived distance between the lives they were living and the kind of aspirational life that Donald Trump was projecting on television. That was the jets, that was Trump Tower, and I think that was partially the suits. That’s what people think a successful person is supposed to look like.

Obviously, I think there’s a huge amount of artifice in his presentation and in the skin tone that he uses, or tries to use. There’s all kind of fakery. I’m not saying that Donald Trump is more authentic in any kind of way, but there is a kind of ineffable phoniness to the ordinary politicians standing on a hay bale that is, at the very least, boring. People have seen that for years and years and years now.

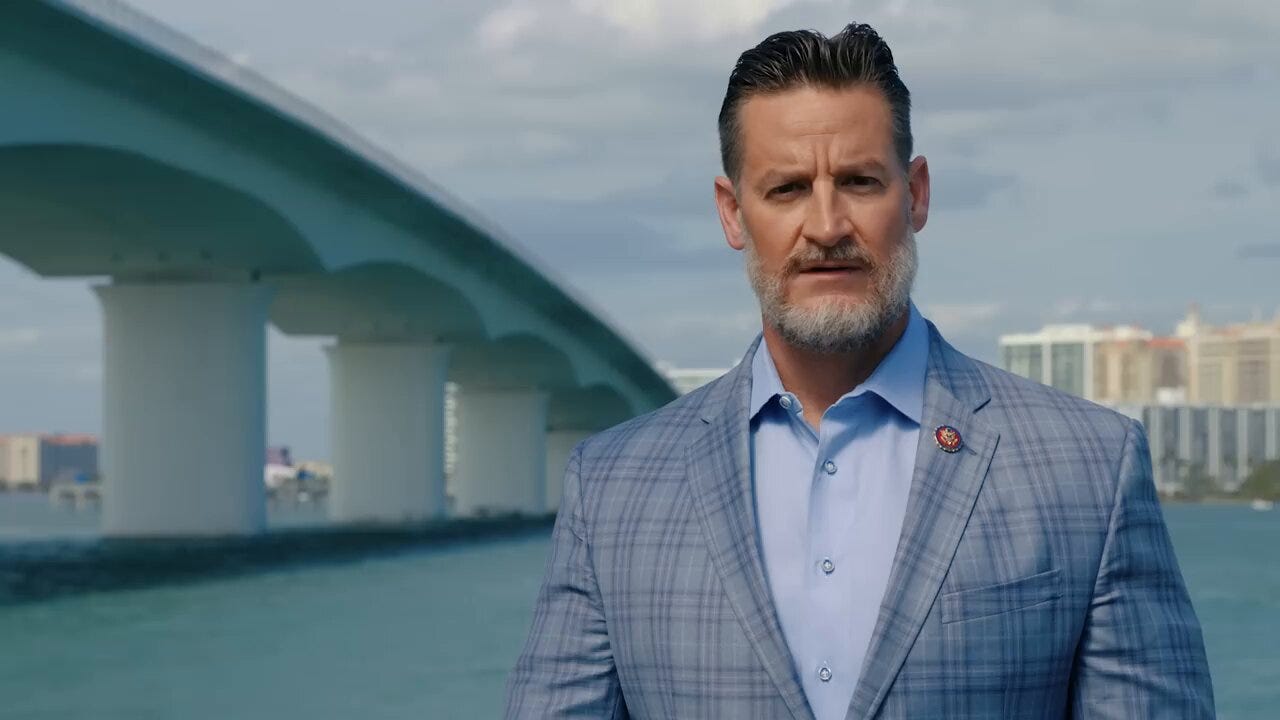

I think one of the things that attracted people to Donald Trump, too, is how novel he seemed—like he wasn’t just going through the motions. And so I think this is a point where people should feel—in all kinds of ways, not just sartorially—liberated as politicians. You don’t have to do this job of pretending. You can do something that is more authentic to yourself and that might even help you connect with voters more than you think. And I think we have politicians who are doing this on some levels, like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, [who is] very stylish. On the right, you have people like Anna Paulina Luna.

You have more people on the right in Congress doing these kinds of suits that I don’t really like—it’s what I call the “Sunday Announcer” fit. Y’know, the checkerboard patterns in pastel colors? Greg Steube is one of the congressmen who does this.

So you know, people are coming to to dress with a little bit more flair. I don’t know if you want to attribute that to anything in particular. But I think that voters are probably a little tired of the whole rolling-your-shirtsleeves-up routine. They don’t think it makes you anymore authentic than the next guy, because the next guy is also doing the same thing.

So yeah, hopefully this means that politicians will make more daring creative choices—if only to break the monotony of the way that political dress has looked for some time now.

Maybe some creativity in the mirror will lead to some creativity in the halls of power.

One thing I will say, though, to add to this, is that I think that the John Fetterman… situation…

I wanted to ask you about him.

[Laughs]

Go right ahead.

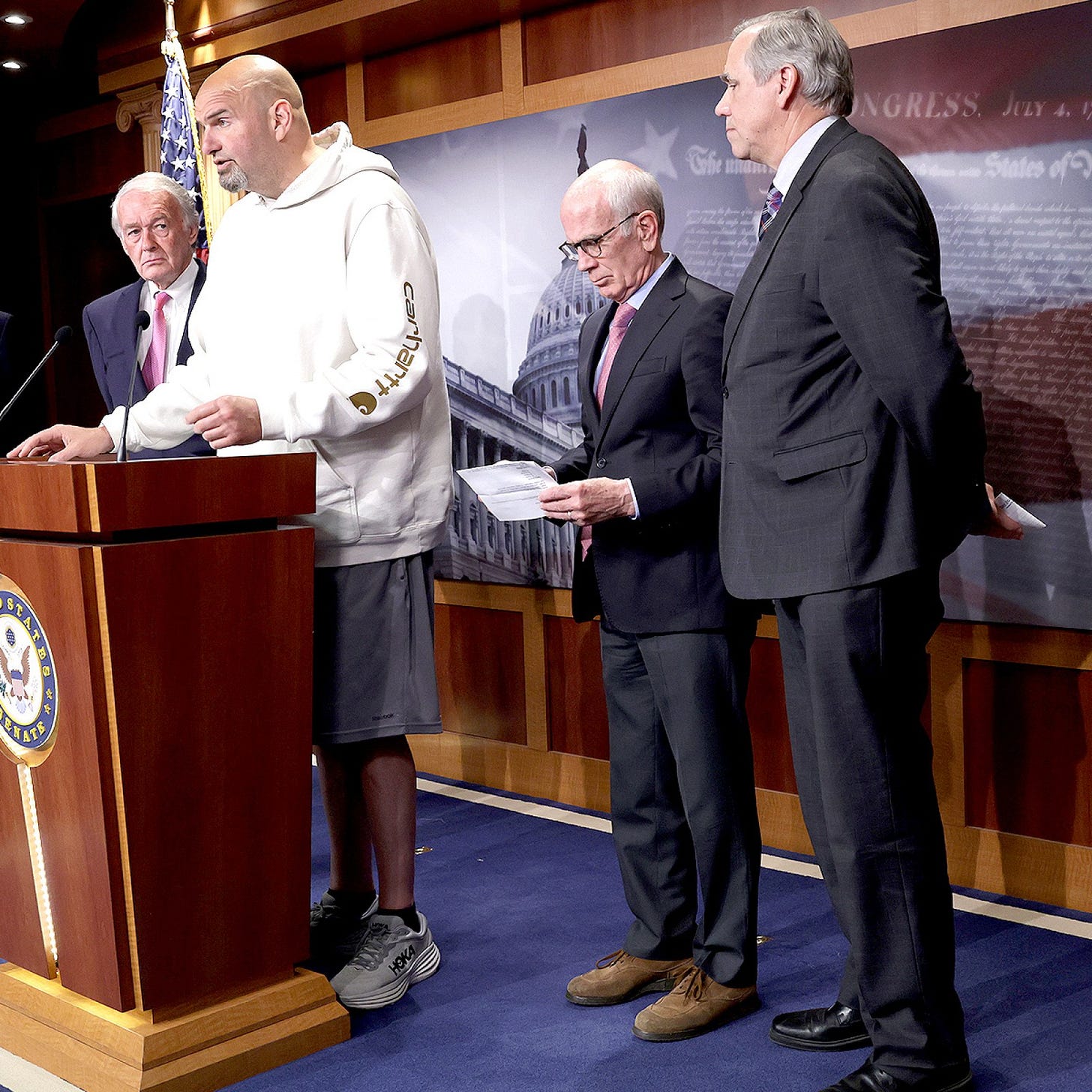

Preempting you there—he is an indication of how misleading some of these choices can be, and how people can often trade a kind of aesthetic perception for investments in the politician’s substance. Substantively, going around in basketball shorts or whatever did not make John Fetterman any more of a “leftist,” or more connected with the electorate. But he certainly traded on that impression for a long time.

Ideally, there’s a kind of balance where people aren’t pandering to you. People aren’t interpreting the choices people make as having anything to do necessarily with the kinds of policies and substance they’re committed to. I think that’s what I’d hope for most of all. Understanding politicians as people through their dress is interesting, especially for journalists, but it can’t substitute for real analysis of what their policies are doing for actual people. Style shouldn’t be used as a stand-in for any of that.

That makes sense. It sounds similar to the critique a leftist might make of identity politics, the Ritchie Torrreses of the world—someone who’s held up as the first gay and Black and Latino rep, but in reality is AIPAC’s biggest defender.

Exactly. And sartorially speaking, the converse of the Fetterman thing is, y’know, I think it would be wrong to distrust Zohran Mamdani because he looks like a more conventional politician and wears a suit and is quite stylish in ways that people on the left have shied away from for some time. I think that that is, frankly, one of the reasons that he’s had this crossover appeal. And I think that matters too.

There are ways that style can be a bridge. If you’re used to hearing from leftists who look a certain way, and then someone doesn’t look that way—it’s an object of interest, right?

One of the things that I find most flattering when I go out to speak to people, or I go out to events, is [when someone says to me], “Before you started talking, I thought you were a Republican.” [Laughs] Which is just a function of the choices that I’ve made sartorially.

What that means to me is there’s somebody who might not have been listening to me if I’d dressed some other way, who I’ve now hooked, because they’re more inclined to take a certain person who looks a certain way more seriously.

Because you’re wearing an Oxford shirt, basically.

Yeah, exactly. If there are people who wouldn’t be listening to a leftist if they’re wearing a hoodie, but they’re listening to me because I wear ties, and I can sort of infiltrate those spaces for that reason, I think that’s worth taking seriously as a matter of political strategy.

Absolutely. I wanted to ask you about Zohran anyways, because I think his appearance has definitely been part of the story. He’s always out there in the videos—especially leading up to the primary in June, when it was like a thousand degrees every day in New York—in the sack suit, and the tie, and the shirt, and the Oxfords and stuff. I interpret that as him trying to use dress as, like you said, a bridge to voters who might be skeptical of the policies, but if they’re being packaged as coming from a sober, legitimate candidate, they might be more willing to accept them. Is that your read on his approach?

I think that’s what he was doing, and he succeeded. Is this the right way to interpret politicians who come before you on a TV screen or social media? I don’t think so. But inevitably, people do make these choices [based on appearance], and I think it behooves people to be attuned to that, to be sensitive to that—at least in electoral politics.

This isn’t a prescription that like, everybody has to get “Clean For Gene” as they did in the Sixties. I don’t think that’s everybody’s responsibility or obligation. But y’know, one of the gaps that the left has had, or one of the challenges that it’s had as a movement, is that as much as people like people like Bernie Sanders—they think he has the right policies maybe, that he has the right concerns—there’s this credibility gap where people who believe all these things don’t necessarily believe that Bernie Sanders would be a good president, or that he could do all those things if he were president.

A lot of that is aesthetics. A lot of that is the way the guy looks to people who watch CNN and MSNBC, and the way they’re used to all the other people who appear on their television screens looking. And I think that that is something to be played with, worked through, and addressed partially through aesthetics. And I think that’s one of the reasons that Zohran has probably been as successful as he has.

Now, I don’t think it’s exclusively something you can chalk up to style. If he didn’t have the right message, I don’t think that would matter very much at all. But the viability of that message, and that it’s being carried to a broad swathe of New York voters, I think has something to do with his aesthetic presentation. Some of that is his social media efforts, and I think some of that is his personal style.

Part two of my interview with Osita coming next week

Buy “The Right of The People” today

Follow Osita on Bluesky and X.com