In Concert: Destroyer, Cass McCombs, Big Thief, Blake Mills

Play A Song For Me 001

Fall is here, finally.

Short days of grey skies mean I’ll finally get to bust out the jackets and trousers I’ve been longing to wear since February. Along with the cooler weather comes another benefit, at least here in the greater Bay Area: concerts. September, October, and November are always densely packed with great gigs. This year is no exception.

A few weeks ago, I realized I had a major run coming up—four shows in five nights, with the motion picture event of the year wedged in there for good measure. What follows is a running diary of these events and associated thoughts, feelings, and photographs.

Tuesday, September 23rd

I drove out to Berkeley to catch Blake Mills and Pino Palladino.

A few weeks ago, Blake and Pino dropped That Wasn’t a Dream, the follow up to 2021’s Notes With Attachments. Both records are spacey, technically spectacular instrumental(ish) jazz(ish) odysseys. I’m much more familiar with Blake’s work as a rock artist—the guitar solo on “Skeleton Is Walking” remains undefeated—and producer of other rock artists, but I’ve been digging this side of him (almost) just as much.

Dream is smooth, creamy, rhythmic, playful. It’s also digestible, a seven song set that clocks in somewhere south of 38 minutes. It’s been a great accompaniment on nocturnal BART rides, transiting into and out of Bay Area bedrock. Consider this a full-throated recommendation to any skeptical rockists out there.

The show was at some place called The Freight, which I’d never been to before. Turns out it’s a jazz club a block off the main Shattuck/University drag—not the kind of place I typically find myself. Still, it was a great room: small, fully seated, tons of space above your head for sounds to bounce around and blend into something strange rangy. The sold-out crowd was rapt and respectful, a pleasant change of pace from the typical chattering set you find at rock gigs.

The set was viscous and iridescent and warm. Everyone was operating at peak performance, fully locked into their own world while simultaneously in tune with everything else happening around them. The guy next to me actually laughed out loud a few times, typically at a particularly nimble bit of percussion from drummer Chris Dave. Very vibes, particularly with the stubborn heat still lingering in the air long after dusk; this just so happened to be the hottest day of the year for the Bay.

After the crowd cleared out, Blake and I shot the shit for a bit. He came through on Never Ending Stories last month to rap with me about the brilliant Cass McCombs, but it was great to meet IRL—as much as I love podcasting, you can’t beat a handshake. He’d been wearing a Hejira cap when we spoke previously, and I mentioned how much sense that made after seeing him go full Jaco Pastorius on the fretless bass. Turns out Blake’s got some of the type of gear Pastorius used to use, which he puts to good use in his performances with Joni Mitchell. Small world.

Wednesday, September 24th

I went downtown to catch Destroyer at August Hall.

I’ve been attending Dan Bejar shows religiously for nearly two decades. He’s one of the few artists I still consider “can’t miss,” even when he’s playing in smaller, stripped down configurations. This is how I saw him the two most recent times: as a duo in early 2024, and as a trio opening for Father John Misty earlier this year. These are quiet, compelling performances, full of catalog cuts from ten, fifteen, twenty years ago—Bejar can command a room with nothing more than his voice and his hair.

The real treat, however, is the full band experience, when Dan “goes electric.” Every time I catch one of these shows, I’m convinced it’s the best I’ve ever seen. Unfortunately, they only happen so often, typically during album cycles: it’s expensive to transform your one-man art rock project into a seven-piece colossus.

Fortunately, this year’s an album cycle. In March, Bejar released Dan’s Boogie, the fourteenth Destroyer record. It is, as always, excellent, full of tangled knots of language and undeniable melodies and rich, dense arrangements, all guitars and gleaming synthesizers and reverberating horns. It’s music made to be played by the big band. The numbers just have to pencil out.

A sense of precarity hovered over the journey there, the undeniable feeling that mechanisms which once worked were beginning to fail. I got off BART at Powell, across from the San Francisco Center, an enormous mall on Market that has collapsed into near-total vacancy over the past several years. The streets were dim and empty and full of unsettling heat—less than the day before, but still very much present.

August Hall is in an odd part of town, right in the thick of “classic San Francisco.” It’s gorgeous territory, certainly, full of old-growth office buildings and dark little dives, but it tends to empty out once the sun goes down and the professionals flee back to North Beach, the Richmond, and the Rockridge/Temescal corridor. I queued up outside alongside my fellow thirty- (and forty-, and fifty-) something men, made my way through a maze of low ceilings and staircases into the main room. Someone’s put plenty of capital into August Hall, but it remains somewhat antiseptic, vaguely off-putting for reasons I can’t quite explain.

Jennifer Castle opened the show. She’s got a knockout voice, but it was hard for her to reach the entire room without a band. Surely, economic constraints are in mind on this tour, which will wend its way south, then east, then north, then east again, then north further still, all the way to Montreal, then south down the Eastern Seaboard, then west and north and west and north, like stairsteps across the middle of the country, before finally finding its way back to Vancouver, where Bejar lives. It’s an odd, curlicue route—Milwaukee to Minneapolis to Cleveland?—but apparently efficient enough. There only seems to be one bus, but one is certainly better than none.

All these concerns were forgotten the instant the band took the stage. Destroyer live is many things, but it is one thing above all else: LOUD. “The Same Thing As Nothing At All” exploded like a bomb, blowing the crowd back from the stage. You could feel it deep down in your gut: physical, involuntary, wholly satisfying. This is what rock songs should sound like.

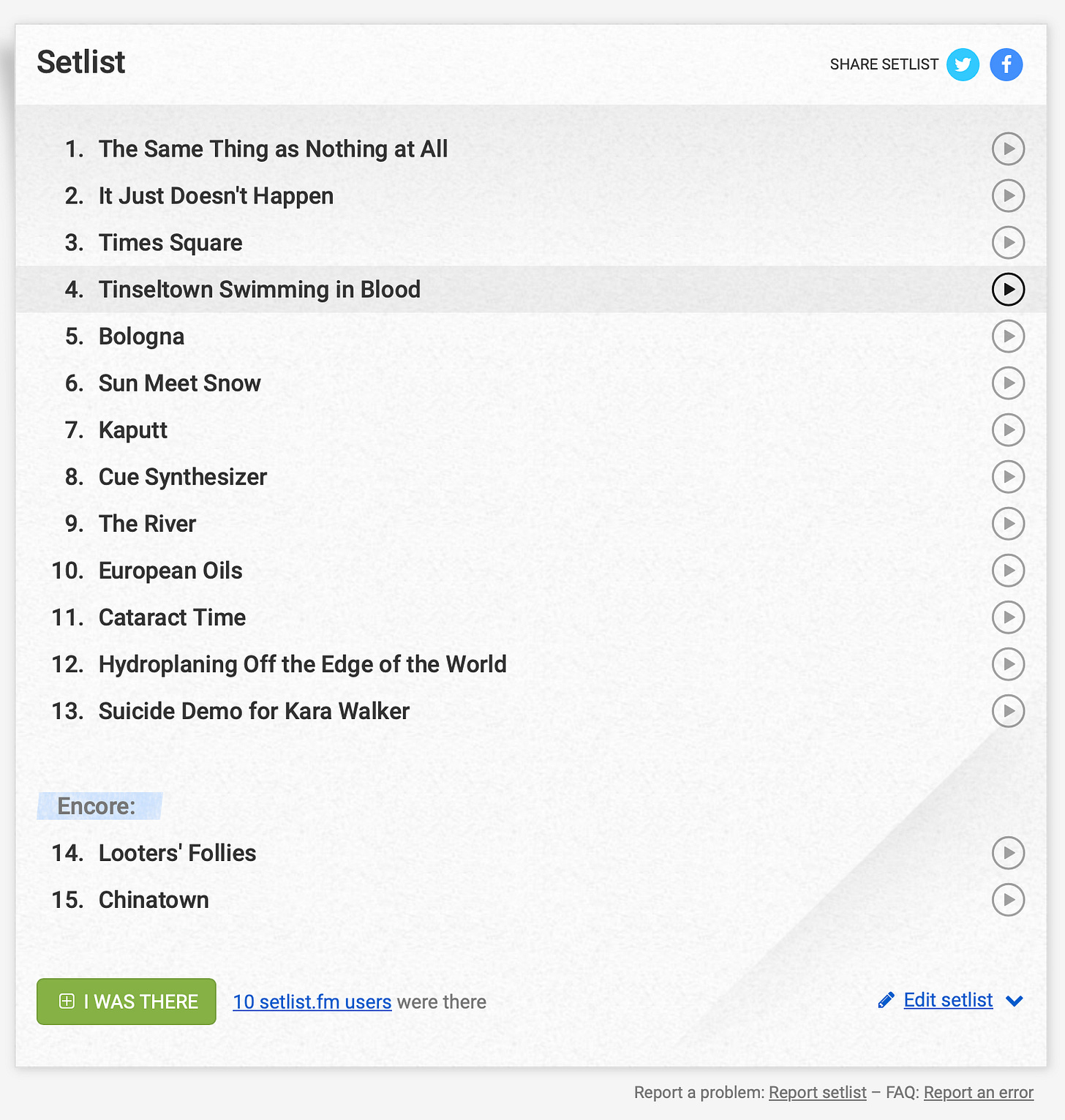

From there, the band was off to the races, banger after banger after banger—pure gas, all night. The Dan’s Boogie material sounded incredible: pummeling at times (“Hydroplaning Off The Edge of the World”), lush at others (“Cataract Time”), always ear-splitting. Bejar managed to thread a delicate needle in selecting songs, spotlighting new tunes while also effectively playing his greatest hits. Dig this setlist:

The Kaputt material in particular was a revelation. I don’t listen to album too frequently these days—I must have heard each song a thousand times by now—but when the sequencer whirled to life and the guitars swooned and the band launched into the title track, I felt myself melt. Everyone around me seemed to feel the same way. All sounds like a dream, indeed.

Bejar is one of the great frontmen of the 21st century. He’s aware of the part he’s there to play and he plays it perfectly every time out, flouncing around the stage in a positively torched OCBD. The drama comes from his contrast with the band: the laissez-faire frontman and his murderer’s row of musicians. He’s fully aware of the power of the sound behind him, but he’s plays it like its expected, entirely de rigueur, crouching down at the foot of the stage to sweep his mane back, swig some wine, maybe crack the slightest of grins. He knows exactly what he’s doing.

We got a double shot of Destroyer classics for the encore, “Looters’ Follies” and “Chinatown,” and then it was over, far too soon. I’ll see them again in two years time, hopefully.

Thursday, September 25th

Back out to Berkeley for Big Thief.

I’m sorry to say this was the first time I’d ever seen them. I was a Big Thief agnostic until the undeniable Dragon New Warm Mountain I Believe In You. Their latest record, Double Infinity, is even better—“the unmistakeable work of a band with nothing left to prove.” I seem to be on my own in thinking that, at least among music critics, most of whom agree that the record is a step back, and perhaps the first indication of an oncoming decline. And that’s just fine: more good music for me.

I met my friend Jordan down in town to grab a slice of pizza before the show. The heat of the last couple days had finally dissipated, and the streets were packed with undergrads and DoorDashers and skateboarders. People seemed to be responding to the change in weather, moving faster to catch up on everything they had failed to accomplish on scorching eighty-degree days.

We made it into the Greek Theatre just as the openers kicked off their last song. The place was already packed, so we trudged up to the terraced lawn above the amphitheater to settle in at the very top. This crowd was everything the Destroyer crowd was not: young, chatty, mostly female. Going in, I didn’t have a firm picture of the typical Big Thief fan, but it immediately became clear that the band resonates most with earnest, yearning Zoomers. Whatever anyone may think of the latest record, the fact that they can summon tens of thousands of twenty year-olds for a night of live rock music is an achievement.

And it’s very good rock music. The set was relatively short, focused primarily on material from the new record. Double Infinity is a busy, buzzy record, full of zithers and tape loops and laughter. The strength of the songs lies in their messiness, the overwhelming wave of sound produced collectively by six, eight, ten people packed tight into a little studio. It’s not something that necessarily translates to the stage, especially when Big Thief remains so defiantly simple: four players, zero video screens, everything played live.

This arrangement means they’ve had to reinvent these new songs already. In most cases, they work great. “Los Angeles” already sounded like a live classic, rousing and catchy and effortlessly romantic. “No Fear,” one of the haziest songs on the record, was refashioned into something much heavier, built around sledgehammer chords from Buck Meek. Some songs were still a work in progress. “Incomprehensible” was a bit thin, in need of something to compensate for all the missing studio clatter, and I found myself missing Laraaji’s huge vocals on “Grandmother”—but hey, that’s a tough one to fake.

I never caught Big Thief with Max Oleartchik, but it’s clear that new bassist Joshua Crumbly fits right in. In our recent conversation with Buck on Jokermen, he spoke glowingly of Crumbly’s talent and presence. After seeing them perform, it’s clear why. Crumbly offered a steady foundation throughout the night, even as certain songs wobbled. Judging by the huge cheers it elicited, his mondo bass solo on “Words” may have been the highlight of the night.

There were a couple speedbumps at certain points. Adrianne Lenker in particular seemed to be in a strange place, like she had things she wanted to say but not the words with which to say them. It was difficult to tell what was going on from way up high, but according to firsthand reports, there was some strange energy in the crowd. Still, the band powered through. By the time they wrapped on “Spud Infinity,” the whole bowl was fully on their side, singing along to every word.

For now, it seems that Big Thief is in state of becoming. They’re figuring out how to be a band again, how to stand on three legs instead of four. It isn’t always successful, but it’s thrilling nonetheless. The best shows are those in which anything can happen. Sometimes, necessarily, that means a mistake, a miss, a flub. That’s alright. You take the bad with the good—especially when there’s so much of the latter.

Friday, September 26th

A refreshing night off from shows, which meant I could catch One Battle After Another.

I went down to the Metreon to catch a 70mm IMAX screening with my men-only book club, which exists as a valiant defense against a) the male loneliness epidemic, and b) the “men don’t read fiction” narrative. In preparation for OBAA, we just finished reading Vineland—the first Pynchon novel I’d actually managed to complete. I loved every page, from the kaleidoscopic cultural history of 20th century California to the false flag Godzilla attack to the People’s Republic of Rock & Roll to the Galaxy of Ribs to the shockingly tender final page, which brought tears to my eyes for the first time in months. I had no idea how the events of the book would translate to the screen, but I was excited to find out.

As it turns out, they weren’t. OBAA may have been “inspired” by Vineland, but it’s a mistake to consider this an adaptation of the book in any sense. I may have more to say about the film on an upcoming podcast, so I’ll reserve most of my comments until then. For now, I’ll just say that it’s another PTA masterpiece, yet it left me feeling ever-so-slightly cold—the exact opposite of what I expected. This tweet from Eric Deines sums up where I’m at currently:

That said, impeccable needle drops, as always. I don’t wanna do your dirty work no more…

Saturday, September 27th

Up to Sonoma, then out to Bolinas for Cass McCombs and associated acts at a benefit organized by esteemed NorCal promoters Folk Yeah.

Bolinas is a tiny township tucked into the southeastern tip of the Point Reyes peninsula. You drive up and into the Marin Hills, then wind down toward the coast through dense stands of redwoods and endless eucalyptus, finally emerging onto a small lagoon, the surface of which sits, threateningly, just a few feet beneath the road. Small wooden houses are arranged along unpaved roads with alphabetical, botanical names: Aspen, Birch, Cedar. Some of these homes have clearly had a lot of money pumped into them, others are on the verge of collapsing in on themselves. There appear to be precisely zero restaurants. Think Sea Ranch divided by Eureka and you’re not far off.

The show took place in, and was a benefit for, Mesa Park, a small municipal complex on the outskirts of town. Folk Yeah co-presented with Parachute Days, a micro-promoter named after the enormous parachute tent that’s set up at all their events. Anyone who’s been around long enough (me) might remember previous Parachute Days gigs at nearby Love Field, including the last couple west coast Woodsists Fests. These gigs have an extraordinarily chill vibe: blankets spread out all over, kids and dogs running higgledy-piggledy, no phone service whatsoever. It’s exactly what I’m looking for out of live music these days, the complete antithesis of corporatized festivals held in “scene”-y locales. Next time you see a Folk Yeah gig in some way off the map spot, do whatever you can to get there. It hardly even matters who’s on the bill.

Of course, it doesn’t hurt to have one of this century’s preeminent artists headlining. This was my first chance to hear some of the material from Interior Live Oak, Cass McCombs’s latest release. Live Oak is one of the year’s best records, an entire ecosystem of rock songs—“a California of the stereo,” per my review for Aquarium Drunkard. Bolinas promised to be the perfect setting to hear some of it performed.

My wife Grace and I met Jordan and his wife Madeline there around 2:30. We posted up by the booth and let the afternoon wash over us, nursing tallboys of dry cider, noshing on Asian pears that someone had left in a box on the ground, free for anyone to take. People tossed footballs and slung frisbees while performers came and went onstage, utterly unconcerned with how much attention was being paid. Time passed gradually, then suddenly, and then there was Cass.

The set was suitably stripped down, just McCombs, his bass player, and the occasional click track. He didn’t need anything more: the bones of the songs are strong enough. “Missionary Bell,” one of my favorites on the album, was a particular highlight, all chiming chords and effortless melody. New tunes like “Priestess” and “Peace” cohabited easily with classics like “Bum Bum Bum” and “Big Wheel.” Like the Destroyer set, it all added up to something greater than the sum of its parts, a simultaneous look back and look ahead. McCombs and Bejar sit together neatly as obscure, compelling lyricists who also happen to be world-class rockers. The music they make couldn’t be more dissimilar, but it all hits the same pleasure center in my brain.

The sun began to set midway through, and lights came on, and the tent transformed into something strange and dark and warm, a handcrafted spaceship marooned on a distant forest moon. Cass shifted between electric and acoustic-electric guitars while wild packs of children roamed at his feet, dancing and shouting and falling down in time to the music. For a moment, the world outside ceased to exist. This is the magic of these gigs, what makes them worth rearranging a day around.

They always end too soon. Before we knew it, we were back on the road, speeding south along Highway 1 in the dark through Stinson Beach and Muir Woods and Mill Valley, back to reality and the hum of the freeway and no music at all.

Glad you caught Jennifer Castle live, she's the best! Check out her records, they're all good.

I saw One Battle After Another with my mom and the two of us walked out of the theater after having both cried at least three times (good tears). I dig the idea of the men’s bookclub seeing a movie that ended up being about parental instincts and their attendant follies, or somethin.

I saw it again last night after seeing it when it first came out on a date with a single mom (I needed to see that fuckin car chase/THAT UP AND DOWN THE HILLY ROAD shot agaaaain) and being close to someone who has had to handle that shit there were some devastating moments/choices/voicings that were cathartic in the classic “this is what a movie is supposed to do” way that she hadn’t seen represented so big and non-didactic.

Long way of saying I think it’s inneresting that you saw it with a men’s book club and I saw it with two different strong women and that drop into THAT Tom Petty song at the end kinda hits ya over the head in a good way. It was very cool to see it through someone else’s eyes? I think a lot of mixed families and single parents and parents in general will feel seen in a way that I haven’t seen a slapstick action movie allow.

Anybody in your men’s book club a single parent? Would be inneresting to cross-check with yr bros

Love yr shit, thanks Ian

and never forget Paul Thomas Anderson’s children are Minnie Riperton’s grandchildren so when you re-read this play https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9I3UTG1dSTc