The Entertainer

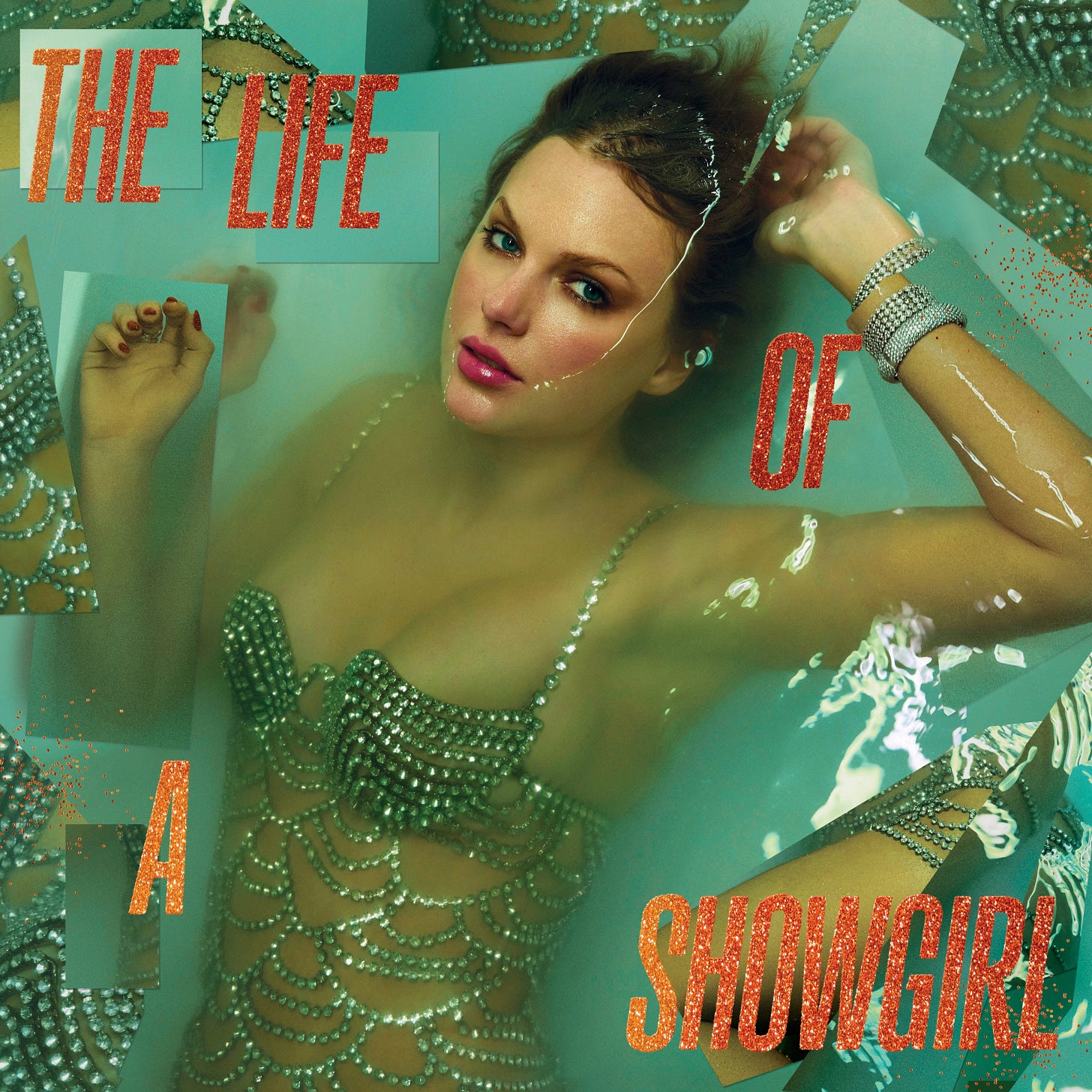

On Taylor Swift's "The Life of a Showgirl"

I am a man torn between worlds.

On the one hand: certain podcast co-hosts of mine, whose opinions I respect a great deal, who detest Taylor Swift’s latest record. This seems to be the prevailing opinion all across my X (The Everything App) timeline, most of which is composed of music critics, politics obsessives, and general take-slingers: that The Life of a Showgirl is laughably bad, loaded with corny lines, pseudo-serious self-mythology, and a particularly baffling ode to the penis of one Travis Michael Kelce.

On the other hand: my wife, and my sister (age 30), and my other sister (age 14), and the untold millions of Taylor Swift fans the world over. To them, Showgirl is more than a record—it is an event. It is music that will accompany them throughout the next several years, if not longer; music that will etch itself into their memories through sheer repetition, becoming the soundtrack to whatever phase of their existence, good or bad, they happen to be living through.

In that way, it’s similar to my relationship with the work of Bob Dylan. Through his art, he has transformed my reality, made me into a wholly different being than I would have otherwise been. I will follow him anywhere—even through five LPs of American songbook covers and an 18 minute song about the assassination of John F. Kennedy. Especially through an 18 minute song about the assassination of John F. Kennedy.

I’m not, apparently, the only one to draw this comparison. My friend Ray Padgett clocked a little chatter about Bob/Taylor comparisons in the comments of Stereogum’s write-up of Showgirl:

Per user “Goner,” Showgirl is Taylor Swift’s New Morning, a record “thousands of miles away from… the peaks of her career.” I understand the general thrust of the claim: Showgirl seems to be a consciously low-stakes effort, something to be enjoyed rather than studied.

Still, New Morning doesn’t seem like quite the right comp. That record was released just a few years after Bob’s legendary mid-sixties run—less time than it took Swift to go from the Folklore/Evermore double-shot (clearly not the high point of her career) to this latest release. New Morning was also received as something of a return to form at the time, a pleasant half-step toward audience expectations after the exasperating Self Portrait. Certainly, there would have been displeased listeners, but it’s difficult to imagine “If Not For You” or “Day of the Locusts” conjuring the same amount of vitriol as some of these latest Swift songs.

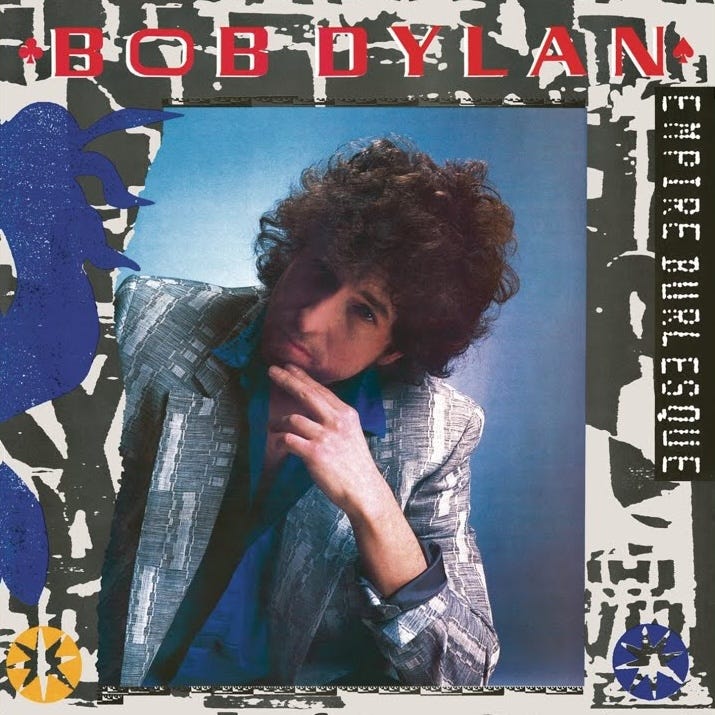

To me, the more appropriate comparison in Bob’s catalog lies further down the line: 1985’s Empire Burlesque. That record arrived a decade after Blood on the Tracks, about the same amount of time between Showgirl and 1989, Swift’s last universally-beloved release. Like Empire, Showgirl’s cover features its author in an uncomfortable pose, clad in an unconvincing costume bearing little relation to the music within. Both records were also released a year into the second term of unprecedentedly brutal right-wing austerity regimes headed by senescent entertainment industry veterans—but that’s another conversation.

The strongest similarity between Showgirl and Empire is in the writing. Swift is being pilloried for any number of lines on the new album, none moreso than the first verse of “Eldest Daughter:”

Everybody’s so punk on the internet

Everyone’s unbothered ‘til they’re not

Every joke’s just trolling and memes

Sad as it seems, apathy is hot

Everybody’s cutthroat in the comments

Every single hot take is cold as ice

When you found me, I said I was busy

That was a lie

This is, admittedly, awful. The lines about Travis Kelce’s member, complete with nonsensical reference to the podcast he hosts with his orc brother, aren’t much better:

And baby, I’ll admit, I’ve been a little superstitious

The curse on me was broken by your magic wand

Seems to be that you and me, we make our own luck

New Heights of manhood

I ain’t gotta knock on wood

“You will wind up peeking through her keyhole/Down upon your knees,” this is not.

But neither is the language on Empire:

He was a clean-cut kid

But they made a killer out of him

That’s what they did

He bought the American dream but it put him in debt

The only game he could play was Russian roulette

He drank Coca-Cola, he was eating Wonder Bread

Ate Burger Kings, he was well fed

At the time of its release, songs like “Clean Cut Kid” made Empire Burlesque an easy target. There’s something almost indecent about it, hearing the man behind “Blowin’ In The Wind” whinging on about Burger Kings.

Today, however, this daffy bullshit is what makes the record so enjoyable. It is a snapshot of a diminished Bob Dylan, an artifact of his “How Do You Do Fellow Kids?” era. For listeners coming to the material decades down the line—listeners like me—that makes it all the more thrilling. It is a chapter in the story of the most extraordinary mind of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, as essential as The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan or Highway 61 Revisited or “Love And Theft.” It is part of the process.

To be sure, I don’t consider Swift and Bob to be artists of the same caliber (I’m not sure “artist” is even the right term for her). But I can’t deny that many, many people do. Her cultural footprint is massive; she means the world and more to millions (billions?). I can already imagine some Jokermen equivalent thirty years from now that delights in Swift’s missteps and moments of weakness the same way Evan and I relish every Bob oddity, from the Live Aid appearance to “TV Talkin’ Song” to whatever the hell this is:

My journey with Bob has given me a different perspective on icons like Swift. I’m compelled to defend her decision to release distasteful, critically-reviled music, even as I acknowledge that said music is not particularly good. After all, Empire Burlesque, Knocked Out Loaded, and Down In The Groove eventually got us to Tempest and Rough & Rowdy Ways. Who’s to say Swift won’t make the same journey? It isn’t likely, but neither was it for Bob.

Another Boomer icon is an even better comparison for Swift, someone with whom her attitude, popularity, and general ~vibe~ align uncannily well: Billy Joel. Both outsiders who broke in to the industry from peripheral genres, both massively successful, both deeply self-conscious.

Like Swift is today, Joel was loathed by the tastemakers of his era. The music he made didn’t fit neatly into the rock paradigm favored by Rolling Stone, Creem, and Robert Christgau, and it was routinely written off as inconsequential, pap, a triviality. Even as he ascended to the absolute apex of fame and fortune, critical appreciation eluded him. The Stranger, his breakout 1977 masterpiece, didn’t even scrape the bottom of The Village Voice’s Pazz & Jop critical survey. He was the Rodney Dangerfield of pop: he couldn’t get no respect.

Frustrated with this reality, Joel made a play for critical acclaim in the early eighties, first with the new wave-influenced Glass Houses, then the self-serious The Nylon Curtain. Both records sold well, but critics hardly took notice. When they did, it was to Joel’s detriment: in a brutal takedown of Glass Houses for Rolling Stone, Paul Nelson claimed he came off like “a particularly obnoxious frat boy who’s hoisted a few too many while trying to put the make on an airline stewardess.” For Joel, it was a losing battle from the start.

Shortly thereafter, he wised up, shifted his focus to pleasing crowds and bedding supermodels. Both of these passions were synthesized on 1983’s international sensation An Innocent Man, which yielded three Billboard Top 10 singles, plus another all-timer in “The Longest Time.” Critics were kind enough to the album, but none mistook it for anything more than it was. Christgau summed up the general sentiment in the first sentence of his capsule review: “His art album having gone platinum and failed to clear bottom line, Joel comes at his poor neglected generation direct, peddling a nostalgia no one will mistake for philosophy.”

This is the key difference between Swift and Joel. No one ever mistook him for anything other than what he was: an entertainer. She, on the other hand, is everything: tortured poet, political activist—hell, even a philosopher.

Unlike Joel, Swift operates in the era of the poptimist, when the most commercially-successful music is also evaluated according to the rubric of high art. Over the past decade, poptimism has provided an important counter-narrative in music criticism, rightfully widening the aperture of artistic legitimacy beyond white guys with guitars. With The Life of a Showgirl, however, we seem to have reached the limits of what this lens can offer.

Poptimism only works when there’s something worth critiquing. Showgirl poses a new and novel question to those who practice it: what if pop music was just pop music? What if was neither good, nor challenging, nor unexpected? What if there wasn’t anything to say about it at all?

The answer, it seems, is just to say anything. The incentives of the attention economy and an unquenchable thirst for “impressions” drive media outlets to make editorial decisions based on what generates clicks, likes, and RTs. Whether what is being said is even worth saying isn’t part of the equation. The Taylor Swift album backlash is a prepackaged part of the Taylor Swift album cycle. It’s a load-bearing part of the take economy at this point. People’s livelihoods depend on this content, so the content must flow.

This is the consequence of the poptimist’s victory: a whole bunch of chatter that all adds up to nothing. Even if you believe that some of Taylor Swift’s music is meant to be taken as seriously as the work of someone like Bob Dylan (a questionable claim, to say the least), it’s clear on its face that this music isn’t. The Life of a Showgirl is meaningless, mindless pop music: nothing more, nothing less. No one should mistake it for anything else.

Here I suppose it’s worth noting that I’ve listened to the album exactly one time—in the car with my wife, driving to and from Costco on Friday night. It sounds perfectly fine: the buoyant synthesizers of 1989 and Lover, a few trap-lite beats, some turn-of-the-millennium pop punk power chords thrown in for the hell of it. I don’t really have any more to say about it beyond that. It isn’t music worth saying more about. The epic takedowns and the rapturous write-ups are all equally absurd.

This isn’t a call to “let people enjoy things” so much as a plea that we recognize there are other, better things toward which to apply our limited mental and emotional bandwidth. Just as restaurant critics have no business reviewing the latest addition to the Taco Bell menu, music critics ought not concern themselves with the latest missive from a billionaire egomaniac engaged to the dumbest man on the planet.

We—as readers and writers both—can just say no.

I also have the Bob Dylan boy and Swiftie girl dynamic with my wife, just want to say thanks for writing this lol except I probably like the new album more than you. But I’ve found my prolonged interesting in Bob makes me feel a lot more empathetic to how excited she is around Taylor. Moving me from a “I hate pretty much all pop music” to “I’ll enjoy what I can enjoy and not care about what I don’t” attitude which I wish more people could join in on. The online hate is so performative, just listen to something you like.

Balanced and equanimous. Great piece.